I’ve read Harry Turtledove’s alternate history novels for years, and I consider him to be one of the masters of the genre – he’s certainly among the genre’s most prolific authors. Alternate history is defined by Wikipedia as “speculative fiction consisting of stories in which one or more historical events occur differently,” and I think that’s an accurate general description of the genre. The real fun in reading an alternate history comes from the “speculation” part of its definition, in tracking how one or two changes in historical fact can lead to massive changes in reality over the next decades or centuries.

|

| Homo erectus |

That’s exactly the approach that Turtledove takes in A Different Flesh, a collection of seven loosely connected short stories that chronologically span over 300 years of American history. Turtledove’s basic premise is that the ancestors of the American Indian population that the colonists found upon their arrival in the New World never make it across the Behring Strait. Instead, the continent remains so isolated until the 1600s that it is still dominated by saber-toothed tigers, wooly mammoths, and Homo erectus, an upright species said to be the ancestor of several more advanced human species. Poor Homo erectus gets to stand in for the real-life abuse suffered by both the Native American population and most of what happened to the Africans who were imported to the colonies later on.

The first story, “Vilest Beast,” features the Jamestown colonists a few years after Captain John Smith has been killed and eaten by a group of wild “Sims” (the name universally applied to the Homo erectus species). By now, both the colonists and the Sims prefer to stay clear of each other, but after one bloody conflict, at least one of the colonists is starting to wonder just how “human” the Sims might be.

The next two stories, “And So to Bed” and “Around the Salt Lick” follow the evolving relationship between Sims and America’s settlers through the late 1600s, a period during which Sims are captured and sent back to Europe for study. The two species have even by now developed a sign language that allows them to communicate thoughts to each other, and in some cases they develop deeply binding friendships. Overall, however, Sims are still considered animals – and are treated as such.

“Though the Heavens Fall,” the book’s fourth story, is set on an 1804 plantation on which Sims are the slaves doing all the heavy field work and the few black slaves on the plantation are used inside the house. As portrayed in the story, there is a definite class hierarchy on the plantation, and the black slaves are very relieved not to be on the bottom of it. “The Iron Elephant,” set in 1781, is a fun story about the evolution of the steam locomotive and how it eventually would put out of business the wooly mammoth-pulled locomotives of the day.

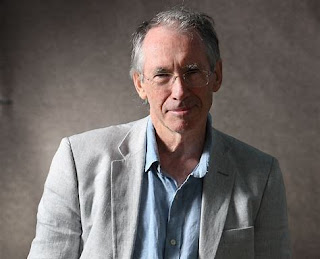

|

| Harry Turtledove |

My personal favorite, though, is “Trapping Run,” a long story set in 1812 about a trapper who has gone farther west than any other explorer of his day. That means that the trapping is excellent, but it also means that when the trapper suffers a devastating injury from a Grizzly, he’s is almost certainly going to die there all alone. And he would have if not for the band of wild Sims who befriend him. This is a touching story, but it illustrates the difficulty of the two species ever truly understanding each other on anything resembling equal terms.

“Freedom,” the last story in the book is set in 1988 (the year that A Different Flesh was published), and it’s the saddest and most disturbing story in the book. By this point Sims are being used in research labs around the world, a practice justified in the minds of researchers by the assumption that the Sims are no more human than any other animal species.

|

| One of the more awful covers |

Bottom Line: Turtledove’s A Different Flesh is philosophically deeper than it might appear at first glance. The Sims are stand-ins for every racially dominated group in the history of the United States, and the author seamlessly slips his serious messages into the book’s seven stories. This one is probably underrated in part because of some of the awful covers the book has had over the decades. Don’t let that throw you off; this one is worth reading.