If the weather holds steady this week, and the potential tropical storm that seems to be developing somewhere around Guatemala doesn't come as far north as the Gulf Coast, I'll be shifting into road trip mode on Saturday morning (the 22nd). That in mind, I'm not sure how much reading I'll be doing, or how much posting, if any. It all depends on the availability of trustworthy wifi connections in the evenings - and how much energy is left in my tank at the end of each day.

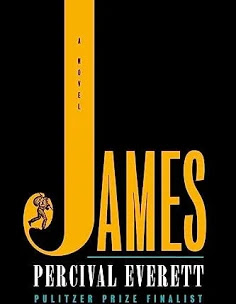

That said, I did finish three books last week (Butterfield 8 by John O'Hara, James by Purcival Everett, and Deliverance by James Dickey), and I have two others in progress to start the new week with (Look for Me There by Luke Russert and The Big Door Prize by M.O. Walsh). As usual, I managed to stray considerably from last week's plan, this time by reading Deliverance sooner than I'd anticipated and by adding The Big Door Prize, a book I had forgotten I even owned before unexpectedly coming across it again one afternoon.

Whether it deserves it or not, Deliverance holds classic status in my mind. James Dickey, a well respected poet, published the novel in 1971 and it was made into a smash hit movie in 1972 starring Burt Reynolds, Jon Voight, Ned Beaty, and Ronny Cox. It was quite a shocking story for its time, especially when it came to homosexual predatory sexual behavior and preempting violence by killing another before they could harm others. I read the book early on, but that was over fifty years ago so I wanted to see if it is as good as I remembered it to be. It is.I very seldom go into "Dollar Stores," but a few weeks ago I popped into one to pick up a small tube of super glue and stumbled upon a shelf with few books on sale for a dollar. The Big Door Prize was the only one that sounded remotely good to me, so I ended up spending a whopping $2, plus tax, on the store visit. It's all about a little town in Louisiana whose grocery store adds a machine charging $2 to sample and interpret the customer's DNA sample to "tell you your life's destiny" and what you are capable of achieving. Now I see that someone turned it into a TV series. |

| A book about a road trip |

|

| Another road trip book |

I'll also be throwing the latest Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine and Alfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine in the suitcase in case I only have time to read a few short stories.