At the risk of sounding like a bit of a fool, I have to say that I was surprised at how much I enjoyed reading Edmond Rostand’s 1897 play Cyrano de Bergerac. The version of the play that I read was translated by Lowell Bair and first published by Signet Classics in 1972. My surprise came from not having particularly enjoyed either movie version of Cyrano that I’ve seen, and assuming that was the play’s fault rather than the fault of the two movies.

A nineteen-year-old book blog offering book reviews and news about authors, publishers, bookstores, and libraries.

Wednesday, September 30, 2020

Cyrano de Bergerac - Edmond Rostand

At the risk of sounding like a bit of a fool, I have to say that I was surprised at how much I enjoyed reading Edmond Rostand’s 1897 play Cyrano de Bergerac. The version of the play that I read was translated by Lowell Bair and first published by Signet Classics in 1972. My surprise came from not having particularly enjoyed either movie version of Cyrano that I’ve seen, and assuming that was the play’s fault rather than the fault of the two movies.

Monday, September 28, 2020

Nobody Hitchhikes Anymore - Ed Griffin-Nolan

Ed Griffin-Nolan is definitely right about one thing. There is a feeling of kinship among those who have ever hitchhiked, even if for only one memorable trip in their relative youth. The memories created by thumbing your way from one state to the next are so vividly implanted that veteran hitchhikers enjoy talking about them even decades later – and they love hearing the stories of others who have experienced the road up close and personal the way hitchhikers, by definition, experience it. I still sometimes think about the time me and another soon-to-be-eighteen-year-old hitchhiked about 275 miles from our home in Southeast Texas to New Orleans on a spur-of-the-moment whim. And that’s why I was initially so intrigued by Griffin-Nolan’s Nobody Hitchhikes Anymore.

Sunday, September 27, 2020

And Nine Months Later...

|

| Fitzgerald |

|

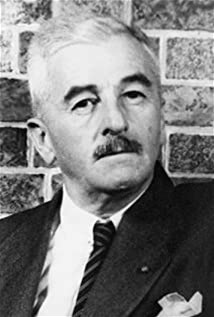

| Faulkner |

Now, maybe I'm the only one who finds this observation to be oddly funny, but I could not resist sharing it with the rest of you. According to one of the calendars I use, Stephen King, F. Scott Fitzgerald, William Faulkner, and T.S. Eliot all had birthdays last week:

- King - September 21,1947,

- Fitzgerald - September 24,1896,

- Faulkner - September 25,1897, and

- Eliot - September 26,1888.

- Donna Leon - September 28, 1942,

- Miguel de Cervantes - September 29, 1547,

- Truman Capote - September 30, 1924,

- Daniel Boorston - October 1, 1914,

- Graham Greene - October 2, 1904, and

- Gore Vidal - October 3, 1925.

|

| Greene |

Saturday, September 26, 2020

Rogue Protocol (Murderbot #3) - Martha Wells

I can’t help but feel a little confused by the third book of Martha Wells’s “Murderbot Diaries.” It’s not the plot or the characters that confuse me, though. It’s more a question of why the whole book - all 158 pages of it - was not simply tacked onto the ending of the previous book – also of about 150 pages – and published as the novel it was meant to be. As it is, Rogue Protocol breaks almost no new ground either plot-wise or character-wise, and I doubt that I would have stayed with it all the way through if I had picked it up as a standalone novella. It was tough enough, at times, to do that anyway because I started to feel as if I were reading a story I had already read, and that only the names of most of the characters had changed.

Thursday, September 24, 2020

The Bookshop on the Corner - Jenny Colgan

Seldom have I been left with such mixed emotions about a book as I have by Jenny Colgan’s The Bookshop on the Corner (perhaps published as Little Shop of Happily Ever After in the UK). I absolutely loved and enjoyed about one-third of the book, and I was pretty much bored with the other cliché-filled two-thirds of it. This is the first title I’ve read by Jenny Colgan, but a quick review of her backlist leads me to believe that she discovered a successful book-selling formula years ago and that she intends to milk it as long as it continues to work for her. Granted, I am not the target audience for a Jenny Colgan book; I know that now, so my reaction to this one is as much my fault as it is hers. Luckily enough, however, I “read” this one via its audiobook version, and Lucy Price-Lewis, the narrator, has such a charming voice and way about her that I continued listening almost despite myself.

|

| Lucy Price-Lewis |

Wednesday, September 23, 2020

The Fighting Bunch - Chris Derose

If Chris DeRose’s The Fighting Bunch were a novel, I probably would have put it down almost as quickly as I picked it up. I would have found the premise of the book to be too farfetched for me to take it seriously, and I would have been unwilling to suspend my level of disbelief to that degree. If nothing else, that shows how naïve I can be about some of the things that happened in America’s s relatively recent past. The book’s subtitle, a long one, says it all: The Battle of Athens and How World War II Veterans Won the Only Successful Armed Rebellion Since the Revolution. But I suspect I’m not the only one who never heard about what happened in Athens, Tennessee, in 1946 after a group of battle-hardened veterans came home and found their county to be completely controlled by one corrupt politician and his gang of criminal-enforcers.

Tuesday, September 22, 2020

$3 Million Worth of Stolen Books Found Underground in Romania

Back in January 2017, in a heist that sounds like something out of the latest Mission Impossible movie, a gang of Romanian thieves cut a hole in the roof of a London postal transit warehouse and "abseiled" 40 feet to the floor, dodging sensors all the way. They were after a collection of rare books being stored in that warehouse prior to shipment to a rare-books auction being held in Las Vegas. They escaped with the books, said to be worth over $3 million, the same way they came into the building.

Now, almost four years later, the books have been recovered, and according to BBC News, thirteen people have been arrested:

The gang is responsible for a series of high-value warehouse burglaries across the UK, London's Metropolitan police said in a statement.

Officers discovered the books underground during a search of a house in the region of Neamț, in north-eastern Romania, on Wednesday.

The find follows raids on 45 addresses across the UK, Romania and Italy in June 2019, investigators say. Thirteen people have been charged, 12 of whom have already pleaded guilty.

The hoard includes rare versions of Dante and sketches by the Spanish painter Francisco de Goya, as well as the titles by Galileo and Isaac Newton dating back to the 16th and 17th Centuries.

It's hard to believe that this kind of thing happens in the real world and not just in movies and books. Apparently, the thieves were willing to sit on the books as long as it took to figure out a way to turn them into actual cash - something that must be near impossible for books as rare and as well documented as these are.

And now, I can't help but wonder if being stored underground in those conditions for almost four years has damaged the books despite how well they seem to be wrapped in the below photo from the Metropolitan Police. High humidity is a book-killer, and from the looks of this underground vault, damp conditions appear likely. Somewhere, an insurance company or two are breathing big sighs of relief about now.

|

| Metropolitan Police Photo |

Sunday, September 20, 2020

The World Has Gone Mad: Banning Harry Potter

In what just may be the final straw that broke this camel's back, I can now officially declare that the world has gone mad.

According to Newsweek (remember them?), one terribly "woke" (a word I detest in this context) bookstore owner in Australia actually thinks it will make her little shop a safer place for customers if she quits selling anything written by JK Rowling. That includes, of course, the Harry Potter books as well as the books published under the Robert Galbraith pseudonym Rowling uses for her crime novels.

So how does this make her little woke-shop a safer place for her customers and their children? Well, according to the genius that owns the Rabble Books bookstore in Perth:

"...we want to talk about JK Rowling. We are always trying to make Rabble a safer space for our community, and part of that is trying not to put books by transphobes on the shelves, when we know about them."

Despite her obvious punctuation problems, this marketing genius goes on to say that all of that regained shelf space is going to be filled with comfort reads that are guaranteed to pull the community closer together by making them feel oh-so-safe as they browse her shelves. No longer will they have to look over their shoulders and wonder if a transphobic person might be sneaking up behind them:

"What I’d love to hear is your suggested alternatives - what are some queer and trans positive fantasy books for young people and crime books for adults?"

Please excuse the sarcasm, and don't get me wrong here. I have nothing against books featuring the "queer and trans" community. That's not really the point. With rare exception, I oppose censorship, and I agree that this woman can sell whatever she wants in her shop. What upsets me in this instance is the way she's going about it. "Cancel Culture" is a horrendous tool used by stupid people, and it's time that the rest of us stop condoning its use.

|

| The Woke Genius, Nat Latter |

Saturday, September 19, 2020

Hieroglyphics - Jill McCorkle

Thursday, September 17, 2020

Who Doesn't Love Books on Books? Here Are 60 Suggestions for You

Anyone who spends time blogging about books and/or reading the dozens and dozens of excellent book-blogs out there, also loves reading about actual books. And we are very lucky that there are so many of them out there: books about books, about bookstores, about booksellers, about bookmobiles, about libraries, about collecting books, about caring for books, and even about "how to read" a book. You name a book-topic, and it's probably out there somewhere.

I had several hours this afternoon during which I had to do the kind of busywork that allows a person to just let their mind wander...so I did. At some point I got to wondering how many book-related books I've read, so I decided to look into that when I got home. Below, is a listing of the ones I could identify (the year listed is the year I read the book, not the year it was published):

- The Bookshop of Yesterdays - Amy Meyerson - 2019

- A Novel Bookstore - Lawrence Cross - 2012

- Mr. Penumbra's 24-Hour Bookstore - Robert Sloan - 2013

- Midnight at the Bright Ideas Bookstore - Matthew Sullivan - 2019

- The Yellow-Lighted Bookstore - Lewis Buzbee - 2008

- The Bookshop - Penelope Fitzgerald - 2019

- The Bookshop of the Broken Hearted - Robert Hillman - 2019

- Paris by the Book - Liam Callanan - 2019

- Book Case - Stephen Greenleaf - 1992

- The Bookman's Tale - Charlie Lovett - 2013

- The Bookworm - Mitch Silver - 2019

- The Bookseller - Cynthia Swanson - 2016

- The Book of Speculation - Erika Swyler - 2015

- The Book Thief - Markus Zusak - 2006

- Booked to Die - John Dunning - 1995

- The Bookman's Wake - John Dunning - 1996

- The Bookman's Last Fling - John Dunning - 2008

- The Camel Bookmobile - Marsha Hamilton - 2007

- First Impressions - Charlie Lovett - 2014

- The Shadow of the Wind - Carlos Ruiz Zafon -2012

- The Prisoner of Heaven - Carlos Ruiz Zafon - 2014

- The Uncommon Reader - Alan Bennett - 2017

- The Thieves of Book Row - Travis McDade - 2013

- Books - Larry McMurtry - 2009

- So Many Books, So Little Time - Sara Nelson - 2007

- The Library Book - Susan Orlean - 2019

- A Passion for Books - Harold Rabinowitz, Rob Kaplan - 2002

- The Care and Feeding of Books Old and New - Margot Rosenberg, B. Mancowitz - 2008

- The End of Your Life Book Club - Will Schwalbe - 2012

- The Clothing of Books - Jhumpa Lahiri - 2018

- Book Lust to Go - Nancy Pearl - 2010

- Modern Book Collecting - Robert A. Wilson - 1988

- So Many Books: Reading and Publishing in an Age of Abundance - Gabriel Zaid - 2017

- How to Read a Book - Adler and VanDoren - 1986

- The Man Who Loved Books too Much - Allison Hoover Bartlett - 2009

- The Maximum Security Book Club - Mikita Brottman - 2016

- Book Finds - Ian C. Ellis - 2000

- Sixpence House: Lost in a Town of Books - Paul Collins - 2003

- Among the Gently Mad - Nicholas A. Basbanes - 2005

- Slightly Chipped - Lawrence and Nancy Goldstone - 2001

- Shelf Life: Romance, Mystery, Drama, and Other Page-Turning Adventures from a Year in a Bookstore - Suzanne Strempek Shea - 2008

- A Pound of Paper: Confessions of a Book Addict - John Baxter - 2006

- My Reading Life - Pat Conroy - 2010

- The Art of Memoir - Mary Karr - 2015

- The Fiction Writer's Handbook - Shelly Lowenkoph - 2011

- Tolstoy and the Purple Chair: My Year of Magical Reading - Nina Sankovitch - 2015

- Leave Me Alone, I'm Reading - Maureen Corrigan - 2007

- A Year of Reading - Michael Dirda - 2016

- How to Read Literature Like a Professor - Thomas C. Foster - 2019

- Reading with Patrick - Michelle Kuo - 2017

- A History of Reading - Alberto Manguel - 1999

- The Year of Reading Dangerously - Andy Miller - 2015

- Reading Lolita in Tehran - Azar Nafisi - 2004

- The Reading Promise: My Father and the Books We Shared - Alice Ozma, Jim Brozina - 2011

- How Reading Changed My Life - Anna Quindlen - 2007

- How Literature Works - John Sutherland - 2011

- The Book on the Bookshelf - Henry Petroski - nonfiction -courtesy of Jeane

- A History of Books - Gerald Murnane - nonfiction - courtesy of Moshe Prigan

- Howards End Is on the Landing: A Year Reading from Home - Susan Hill - nonfiction - courtesy of Kath

- Jacob's Room Is Full of Books: A Year of Reading - Susan Hill - nonfiction - courtesy of Kath

Wednesday, September 16, 2020

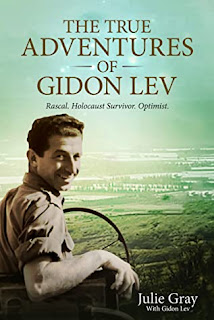

The True Adventures of Gidon Lev - Julie Gray with Gidon Lev

Gidon Lev is an ordinary man who, because of the circumstances of his birth, has lived a truly extraordinary life. That he is even alive to tell us about it today, is perhaps the most amazing thing of all about him because Gidon had no business even surviving his childhood. His adventures began in 1941, when as a six-year-old child, Gidon was transported along with his mother and grandfather to Térézin, a German concentration camp some 30 miles north of Prague. He would still be there at the end of World War II, one of the ninety-two children known to have survived the experience out of the fifteen thousand children imprisoned there during the war.

Gidon Lev is now 85 years old, and he is ready to share his story with the rest of us.

Not only did this man survive a concentration camp where he could have so easily succumbed to disease or some German-inflicted atrocity, he survived both Israel’s Six-Day War and its War of Attrition. He is a two-time cancer survivor. He was married twice and now lives with his “life partner,” Julie Gray, a woman some thirty years younger than him who wrote The True Adventures of Gidon Lev with a mighty assist from Gidon himself. He has six children, fourteen grandchildren, and one great-grandchild – with more to come. The man has certainly had his ups and downs during the last eight decades and, looking back, he’s not always proud of his behavior or the way that he treated some of those closest to him. But then, who is, really?

His story is fascinating, no doubt, but one of the things I most enjoyed about The True Adventures of Gidon Lev is the way Gray (left) takes her readers along for the ride as she pulls the book together from her firsthand observations and Gidon’s notes and papers from his past. As each chapter unfolds, the author shares the circumstances under which it was written, the conversational editing process she led Gidon through, and his emotional reaction to whatever chapter of his life they were discussing. For me, it was hard not to feel as if I were in the room with them, a silent witness to their unique relationship and way of working so beautifully together. Too, I couldn’t help but wonder if the two of them were learning as much about each other and Gidon’s past as I was as a reader. Sometimes, even Gidon seemed a bit surprised by – and reluctant to accept – some of what they uncovered together.

Bottom Line: The True Adventures of Gidon Lev is a firsthand account of one man’s experiences in a World War II German concentration camp. That the experience is told largely through the eyes and memories of a child, makes it even more heartbreaking a tale than it would have already been. That also leaves room for the 85-year-old Gidon Lev to learn things about himself and his experiences in the camp that he had no way of knowing – or remembering – as a little boy. Gidon Lev’s story deserves to be heard, and Julie Gray has done him and his story proud.

(Photo of Julie Gray and Gidon Lev credit to Julie Gray)

(Review Copy provided by Author or Publisher)

Tuesday, September 15, 2020

Shane - Jack Schaefer

Sunday, September 13, 2020

Today's Smile: Heywood Broun vs. F. Scott Fitzgerald

Apparently, critic Heywood Broun (1888-1939) did not at all care for F. Scott Fitzgerald's This Side of Paradise when it was first published - and he never changed his mind. Broun not only gave the book a bad review, he continued to take shots at it in several later newspaper columns, including one written about his attendance at the 1920 Yale-Princeton football game. Broun worked as a sports writer for part of his career so he knew what he was talking about - but he still couldn't resist taking another shot at Fitzgerald, himself a Princeton graduate.

Who doesn't love a longterm spat between a critic and a writer? I know that I do. But what struck me as particularly funny was Broun's take on the value of a college education. As quoted in LOA's email announcement of this Sunday's LOA "story of the week," it went this way:

"...Just before the whistle blew, Captain Tim Callahan of Yale and Mike Callahan of Princeton walked out into the middle of the gridiron. The referee said: 'I guess I don't have to introduce you boys,' and he was right, because the Callahan's are brothers.

Mrs. Callahan believes in scattering her sons. She follows the old adage of 'Don't put all your eggs in one basket.' There is still another Callahan who is preparing for Ursinus. Mrs. Callahan believes that by trying all the colleges at least one of her sons is going to get an education..."

Maybe it just doesn't take much to make me laugh today, or I've finally gone stir-crazy, but I find that to be a pretty good punchline. It worked on me, anyway.

|

| F. Scott Fitzgerald |

Saturday, September 12, 2020

To Your Scattered Bodies Go - Philip Jose Farmer

Thursday, September 10, 2020

Is Late-Onset ADD a Thing?

I'm starting to wonder if it's possible to develop a case of ADD behavior late in life. I've been finding it difficult to actually sit down and read for more than a few minutes without stopping all of a sudden to do one or two other things that suddenly spring to my mind. If that were not bad enough, at the same time that my reading-pace has slowed way down, my book-acquisition-pace seems to be accelerating.

Everywhere I turn, people are talking about books, and I'm jotting down their recommendations as fast as I can. Is there more book-chatter out there these days because of the pandemic? I mean, it's great whatever the cause, but this is getting serious now. Just today, for instance, I watched a livestream from the Carnton house in Franklin, TN, and came away from that with at least half-a-dozen new books on the Civil War that I really, really need to read. And soon.

As of this morning, I was only actively reading two books, both very slowly, as it turns out: Sean Hannity's Live Free or Die, a book that is much better written than I had expected it would be, but is also pretty depressing and scary; and Philip Jose Farmer's science fiction classic To Your Scattered Bodies Go, a book I've read twice before and loved. I am also starting at least two others today by choosing one of the four western novels in the beautiful Library of America volume The Western that arrived in the mail last week. The classic novels are from the 1940s and 50s, but I don't remember ever reading one of them despite remembering three of them well as favorite movies.

The second one, which I've already started, is Julie Gray's The True Adventures of Gidon Lev: Rascal, Holocaust Survivor, Optimist. I have had an electronic review copy of this one for a few weeks, and now seems like the time to read it. Lev was one of approximately 15,000 children sent to the German concentration camp near Prague called Térézin. He and 91 other children survived the experience. Julie Gray was reluctant to take on this project when Lev first approached her with the idea, but now the two of them are constant companions despite their several-decade difference in age. I am definitely liking what I see in this one through the first three chapters.

Also, coming into my hands in the last few days are several other books I'm itching to get into: a nice hardcover review copy of Jill McCorkle's Hieroglyphics; Russ Thomas's Firewatching, a book I was lucky enough to win in a blogger's random drawing; and Martha Wells's Rogue Protocol, the third book in her fun "Murderbot Diaries" that I just picked up from my library this afternoon. And that doesn't even count the dozens of others that I'm keeping handy because I just know I'm going to read them all someday. Yeah, right. Oh, and the new Civil War books I heard about this morning on that livestream I mentioned. I'm about to begin the search to grab each of those, too.

Honestly, I wouldn't have it any other way.